Navigation

Read the first page from the story below:

Sepphira swims five metres below the ocean surface, waiting for her moment. She’s not usually superstitious, but this morning she’d strapped her grandmother’s fifty-year-old titanium diving knife to her ankle, so that something of Allegra was with them today. There are fading photos on the walls of the science facilities of Allegra using the knife to cut ropes and fishing gear from entangled whales, dolphins and turtles: unthinkable today. Ocean protection had been a worldwide priority for the last fifteen years, and in 2040 the need to cut fishing gear from cetaceans is thankfully a thing of the past. Apart from the knife, the rest of Sepphira’s gear is new and hi-tech. She’s wearing one of the latest full-face masks so she can talk into the small microphone when she needs to, and in her earpiece she can hear Leonard speaking to the delegation. She’s aware of each gentle flick of her fins, and the need to conserve her air supply. Today there are important people watching, who will decide the future of the facility. Three generations of Sepphira’s family have poured blood, sweat and tears into the seagrass and marine restoration project; it’s unthinkable that this could all collapse now. She’s desperate for the officials to leave impressed, but nevertheless she’d been thankful when her father had asked her to be the diver today. She knows her nerves won’t be as visible through the tempered glass.

About ten metres away, there is an underwater observation room – built to encourage the tourists to ride their bikes across from the apartments and campsites to spend some precious dollars on a short boat trip and a unique glimpse beneath the ocean. Inside, you feel like you’re standing in a bubble, glass panels on three sides providing a panoramic vista, the lighting dimmed so that divers can only see silhouettes of those inside. Voltage is kept as low as possible, because no one on site wants to squander the solar power – efficient green batteries have come a long way in the last decade but so has the challenge of managing consumption in an award-winning science facility and tourist destination. Besides, when you stand in the dark at this time of the early morning, when the sun is strong and the sky clear, you get the underwater landscape in all its glory: the light playing like tiny sea nymphs along each blade of seagrass, the gentle undulations of each long stem as the current whispers a seagrass extends farther than the eye can see – kilometres further – and Sepphira’s family and the team of scientists and volunteers are responsible for all of it. Marine life and seagrass restoration on this small tourist island has been her family’s home and passion for nearly fifty years. So much has changed, and yet here they are again, desperate for money to sustain and expand the business, and needing to prove themselves.

She knows what her older cousin Leonard will be saying, as he stands somewhere behind those long, polished windowpanes. He will be explaining the vegetational arc of this area: how it has gone from a vibrant meadow to a desecrated and unkempt mess, then back again. She knows his palms will be sweating as he tries to encapsulate, in his thirty-minute timeslot, the immensity of all they have achieved. The careful caretaking of the underwater environment, with meticulous replanting by hand to repair the patches of seagrass ruined by moorings; before the devastations of that first ever Category Six cyclone in 2029 set them back years and a whole lot of funding. The methodical rebuilding, step by step, nothing able to be rushed. And the award-winning inclusion of eco-friendly tourist facilities so that everyone who comes here leaves aware of their project and its fundamental importance to the ecosystem. The story will be laid out like a feast for this delegation with its deep pockets – until, at the end of this day, the Hansen family will find out if their efforts have been good enough. Will their story nourish these people enough for them to want to contribute? Will the project stay afloat for another five years; or will it sink into obscurity, doomed by capricious minds who envision some better use of their funds?

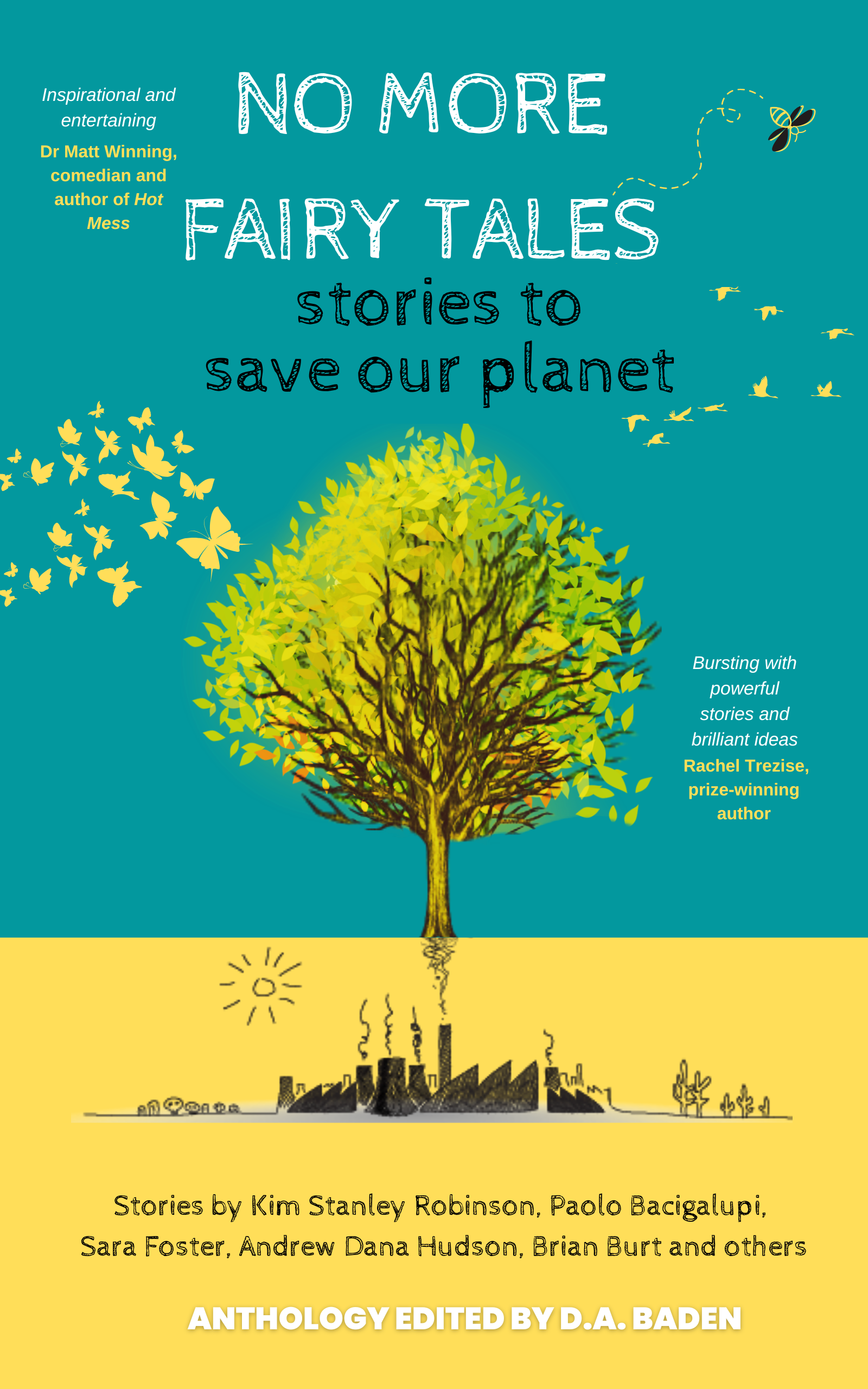

Sara Foster ‘The Envelope’.

Meet the author: Sara Foster

Sara Foster is the bestselling author of seven novels, and her latest, The Hush, is a near-future, female-led thriller about a conspiracy that goes right to the heart of the British government. Her fifth novel, The Hidden Hours, was shortlisted for a Davitt Award in 2018 and has been optioned by TV production company CJZ. Sara began her publishing career working for a time in the HarperCollins fiction department in London, before freelancing as an editor and then beginning her writing career. She is currently a doctoral candidate at Curtin University, studying the representation of mothers in dystopian fiction with young adult heroines.